Home » The illiberal turn in the 2019 Indonesian election

The illiberal turn in the 2019 Indonesian election

WHAT’S HAPPENING?

Jokowi and Prabowo are contesting for the presidency at a critical juncture when Indonesia’s democracy is undergoing a concerning reversal.

KEY INSIGHTS

– Jokowi is likely to win by a narrow margin despite having a significant lead

– The Indonesian election underscores an illiberal trend towards conservatism, populism and intolerance

– Reactive diplomacy and cautious hedging will be the norm of Jakarta’s international conduct in the years ahead

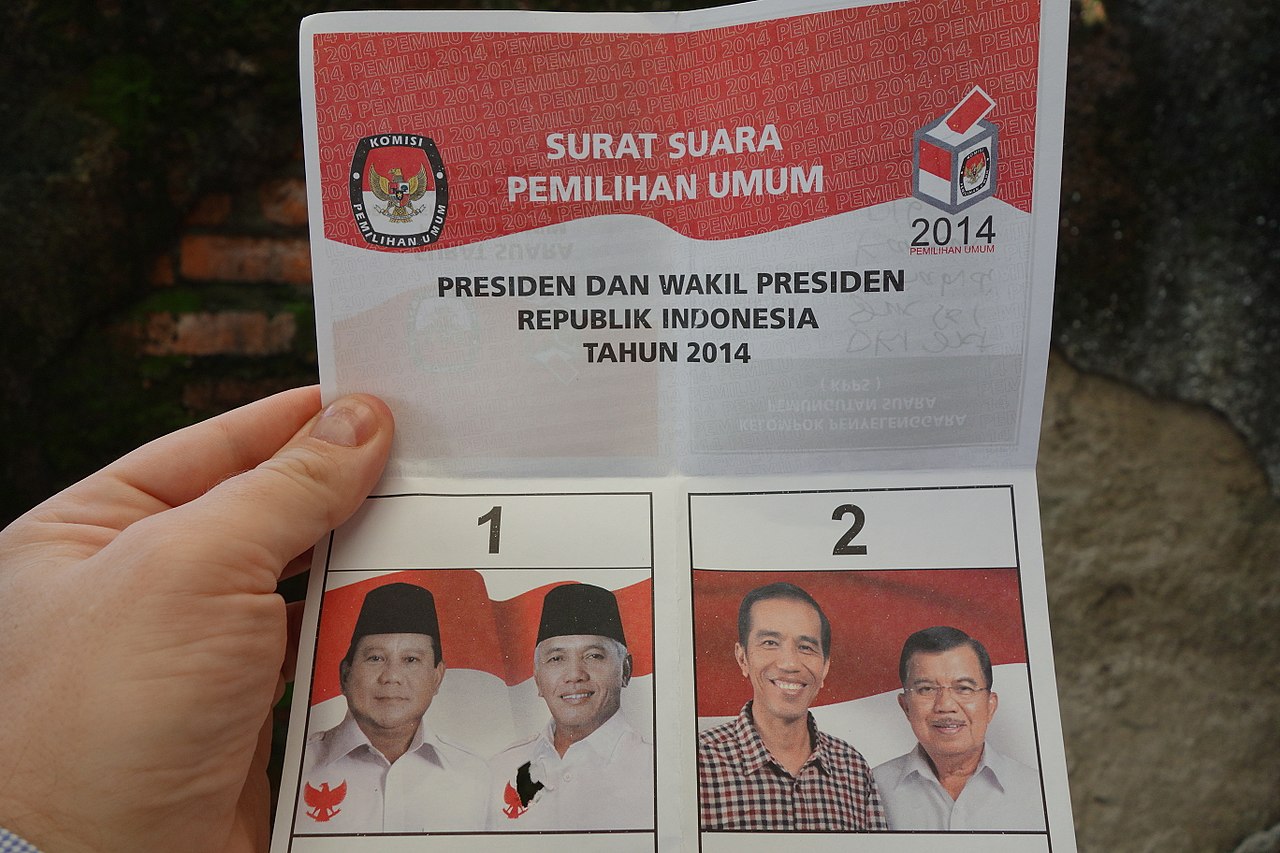

On April 17, Indonesians will once again vote for their next president, an election set between old rivals — incumbent President Joko Widodo (known as Jokowi) and challenger Prabowo Subianto. In 2014, Jokowi beat Prabowo by a narrow margin. In this year’s election, however, the pre-election fervour offers a mixed assessment.

Pre-election polls remain uncertain about the extent of Jokowi’s advantage over Prabowo. On the more optimistic end, a February/March survey conducted by the Saiful Mukani Research and Consulting found Jokowi outpacing Prabowo by 25.8% of votes, a 3% increase from the previous survey in January. On the less optimistic end, another February/March survey by Indonesia’s largest newspaper, Kompas, found Prabowo had narrowed the lead, leaving Jokowi is only 11.8% of votes ahead — an 8.1% decrease from the previous survey in October 2018.

Polls aside, Jokowi undoubtedly has a significant head-start due to his broader coalition of support in the parliament. As the incumbent, he has secured the support of 31 governors from Indonesia’s 35 provinces, including influential figures with the charisma to sway voters and provinces that are traditionally aligned to Prabowo. But this does not mean Jokowi will simply outcompete his challenger. Several issues have placed his leadership on a tight spot.

JOKOWI’S HURDLES

On the socio-economic level, Jokowi failed to uphold his 2014 campaign promise to deliver 7% economic growth. Social inequality has also not abated, trade imbalances have increased due to his preference for imported commodities, and foreign debt has worsened as a result of large-scale infrastructure development spending and reliance on Chinese investment. These issues are unpopular among the middle class, farmers and rural population.

On the political level, Jokowi has reneged on his campaign promise to tackle human rights violations and corruption. Instead, he capitalised on the 2016-17 protests against Jakarta governor Ahok’s alledged blasphemy of the Quran to acquire sweeping executive powers to suppress organisations deemed threatening to national unity. Opposition party members have also been targeted, as well as religious extremist groups like Hizbut Tahrir. The result has been ‘democratic backsliding’; Indonesia fell 20 places in the 2017 Democracy Index, lowering it from ‘flawed democracy’ towards the authoritarian end of the scale.

While Jokowi has undertaken these actions, they underscore a broader rise of Islamic conservativism in Indonesia. Jokowi has thus co-opted the conservatives to improve his electoral chances. Yet this approach and even his choice of Ma’ruf Amin, head of Indonesian Ulema Council, as his vice presidential running mate may not be enough to sway voters. Jokowi’s Islamic credentials remain in question and major Islamic factions continue to favour Prabowo.

These socio-economic and political challenges signify a decline in Jokowi’s traditional voter base, while his new conservative base has not fully taken off. In fact, some of his former voters have threatened to sit out of the election to protest his failure to uphold campaign promises. The prospect for Jokowi’s re-election is, therefore, not as favourable as it seems.

PROSPECT FOR JOKOWI: NARROW VICTORY

Nevertheless, Jokowi is double-digits ahead in pre-election polls. Prabowo has mainly exploited Jokowi’s weaknesses to make a comeback, but his postmodernist approach will not be enough to win the election. Prabowo needs to prove to Indonesians that he is better placed to ‘mak[e] Indonesia great again’. To achieve this, he has promised to support the poor and reduce taxes for companies and individuals, and endorsed as his running mate Sandiago Uno, a middle class-oriented tycoon whose background seem capable of challenging Jokowi in economic expertise.

That said, Jokowi is working to reform his economic policies, meaning Uno’s presence will not necessarily guarantee broad middle-class support. And just as Prabowo has a background that appeals to millennials — a significant minority that has come to represent 40% of Indonesia’s eligible voters — Jokowi has gone to great lengths to improve his social image. Given that Indonesian voters are rarely loyal to particular parties, the odds of influencing this demographic is likely to be, at best, uncertain.

In light of Jokowi’s hurdles, the likely outcome will be a victory by a narrow margin. As for Prabowo, he will need considerable luck, such as a political scandal involving Jokowi, to carry out a ‘black swan’ scenario. The proliferation of ‘fake news’ in social media and the Jokowi campaign’s accusations of alleged Russian and Chinese meddling in the electoral roll may also generate a degree of unpredictably in favour of Prabowo.

REACTIVE DIPLOMACY

Islamic conservatism may not have a linear effect on Indonesian politics. While Jokowi has largely sided with the conservatives, he shares with moderate-pluralists a desire to tackle extremism and terrorism. Moreover, the conservative camp is not monolithic but a range of competing social agents who lack a united and imagined Ummah (Islamic community) and who coalesce momentarily to challenge moderates. The objectives of the camp range from groups like Darul Islam that explicitly seek to establish an ‘Islamic State’ to those like the Prosperous Justice Party that are content with electoral democracy to the Islamic Defenders Front that champions Islamic purity through vigilantism.

Islamic conservatism, in this sense, is unlikely to have revisionist overtones on Indonesian foreign policy. But it may introduce more reactive diplomacy in attempts to defend against the ‘impurities’ of globalisation. Defence Minister Ryamizard Ryacudu’s unfavourable reaction to the LGBT movement is a prime example. Reactive diplomacy is likely to dominant under either presidential candidates, since they have capitalised on the conservative wave to contest the election.

HEDGING BETWEEN THE US AND CHINA

In terms of Indonesia’s broader strategic environment, Prabowo and Jokowi are likely to remain committed to Jakarta’s strategy of hedging against the uncertainty emerging from the US-China strategic competition.

On the one hand, Indonesia’s contemporary alignment with the US is founded upon concerns over Beijing’s rising power and intentions — as well as the historic role the US has played as Asia’s security guarantor against international communism. But the difference in political values (religion and illiberalism) and history (post-colonial sensitivity) has made Jakarta cautious of Washington’s universalist-interventionist tendencies, while the presence of US may come with it the danger of escalating regional tensions.

This uncomfortable relationship means that Prabowo and Jokowi are likely to distance themselves from any explicit alignment with the US against China, even though they may come to rely on Washington to balance Beijing. But Prabowo’s links with Islamic extremists may put him at odds with Jokowi’s ongoing efforts to collaborate with the US on counter-terrorism. A victory by a narrow margin may, however, place Jokowi in a weak domestic position to promote US-Indonesian relations.

On the other hand, Indonesia has found China a necessary but difficult partner to work with. Despite the bilateral territorial dispute with respect to Natuna Island, Jakarta cannot readily confront Beijing. China is Indonesia’s largest trading partner and second-largest in foreign direct investment. This asymmetric economic relationship means that any overtly anti-Chinese diplomatic stance from Jakarta may potentially expose its economy to Beijing’s pressure.

This is especially the case for Jokowi, given his heavy reliance on China to fund his infrastructure projects. As for Prabowo, while he has vowed to reassess Sino-Indonesian projects amidst the fear of a ‘debt-trap’, unfair trade and huge inflows of Chinese workers, he cannot upend the nature of Chinese dominance in Indonesian economy. Thus, the overall structure of Sino-Indonesian relationship will remain stable, regardless of any momentary disruption sparked by Prabowo should he be elected. In terms of defending sovereign interests, both presidential candidates are likely to maintain the delicate balance of muscle-flexing with conciliatory gestures.

Expect Indonesia to pursue a reactive and cautious approach to international affairs as its democracy undergoes an illiberal transformation.

Tommy is a member of the East and South East Asia team. He covers strategic and crisis developments pertaining to the use of force, with a concentration on flashpoints in East Asia.